From the April 2017 issue of GCM magazine:

National trends in land use and environmental practices on U.S. golf courses, Part I

Changes in land use over the past decade have led to reduced acreages of maintained turf, overseeded turf and irrigated turf. Such practices are the basis for lowering the environmental footprint of the golf industry.

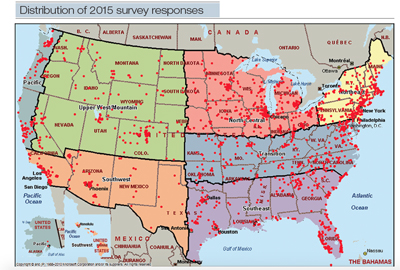

Figure 1. Distribution of 2015 survey responses across the survey’s seven agronomic regions.

Wendy Gelernter, Ph.D., and Larry Stowell, Ph.D.

Read this story in GCM's digital edition »

This study was conducted by GCSAA through the Environmental Institute for Golf, and was funded by the United States Golf Association.

What a difference 10 years makes! As a recently published survey documents, the golf course industry made substantial changes in the way land is allocated and maintained on golf courses in the United States in the decade between 2005 and 2015 (3). Large decreases in the acreages of maintained turf, overseeded turf and irrigated turf have occurred, while increased acreages of lower-input natural, native or unmowed areas have been reported.

In this article, we will discuss these and many other national trends in golf course land use and environmental practices by comparing results from GCSAA surveys that were conducted in 2005 and 2015. A follow-up article, to be published in the May issue of GCM, will summarize how these trends played out in each of the nation’s seven agronomic regions.

Land use, environmental practices and the Golf Course Environmental Profile

Table 1. Median maintained turf acreage, 2005 vs. 2015, for nine-hole vs. 18-hole golf facilities. For each facility type/feature combination within a row, values in bold type with the lower value followed by an asterisk indicate a significant difference between the 2005 and 2015 values at the 90% confidence level.

In 2006, GCSAA and the Environmental Institute for Golf (EIFG) initiated a project to conduct a series of five surveys to document water use, fertilizer use, pest management practices, energy use, environmental stewardship and property profiles. Known as the Golf Course Environmental Profile, the results provided a baseline of information for use in the management of golf facilities, as well as an important tool for communicating within the golf course industry and with regulators, legislators and the general public. Results were published in scientific journals (6-10) and on the EIFG website (www.gcsaa.org/environment/golf-course-environmental-profile).

Table 2. Median maintained turf acreage for public vs. private facilities in 2005 vs. 2015. Within each column, medians followed by the same letter are not significantly different at the 90% confidence level. For each facility type/feature combination within a row, values in bold type with the lower value followed by an asterisk indicate a significant difference between the 2005 and 2015 values at the 90% confidence level.

In fall 2014, the second phase of the Golf Course Environmental Profile began with a follow-up set of surveys that mirrors the previous series. The surveys are being conducted by GCSAA and are funded by the EIFG through sponsorship by the United States Golf Association (USGA). Results of Phase II surveys for water use and conservation practices, nutrient use and management practices, and pest management practices have already been published (2-4). This land use survey is the fourth survey to be released in the second phase.

Figure 2. Allocation of maintained turf acreage on the average 18-hole facility, 2005 vs. 2015. An asterisk indicates a statistically significant difference between 2005 and 2015 values.

How it was done

An initial email invitation, which included a link to an online survey, was sent to 12,951 U.S. golf courses in March 2016, followed by three email reminders. A total of 1,707 completed surveys were received, which represents an 11.3% response. This is somewhat lower than the 18.6% response from the 2005 survey.

PACE Turf and the National Golf Foundation (NGF) were contracted to develop and implement the survey, as well as to analyze, summarize and publish reports on the data.

To gain insights into survey data, respondents were stratified by agronomic region (Figure 1), as well as by golf course type, number of holes and green fees.

Trends in turf acreage

For golf courses seeking to lessen the cost and environmental footprint of their operation, decreasing the acreage of maintained turf is the method that frequently has the greatest impact. Within this framework, the industry has made significant strides over the past 10 years.

Table 3. Projected total U.S. acreage for maintained turf and total facility in 2005 vs. 2015.

- The acreage of maintained turf was reduced by 127,355 acres, an 8.3% decrease since 2005. In other words, maintained turf occupied 63% of total facility acreage in 2005, and 61% in 2015.

- The acreage of winter overseeded turf in the Southeast, Southwest and Transition regions was reduced by 69,029 acres, a 49% decrease since 2005. In other words, overseeded turf constituted 19% of maintained turf acreage in 2005 and 11% in 2015.

- The acreage of irrigated turf was reduced from more than 80% of maintained turf acreage in 2013 to 76% only two years later in 2015.

Maintained turf

Acreage of natural features has increased since 2005, with 46% of facilities reporting additions of these lower-input features, Forests, which are estimated to cover 259,643 acres of golf facilities, are the dominant type of natural feature, followed by native grasslands at 122,567 acres.

Photo by Russell Vandehey

Maintained turf includes all greens, tees, fairways, roughs, driving range/practice areas, turf nurseries and clubhouse grounds.

The maintained turf acreage for a typical 18-hole facility has decreased significantly since 2005, from 99.2 to 95.1 acres. There were significant decreases in acreages for nine-hole courses as well, which reduced maintained turf from 42.5 acres in 2005 to 37.6 acres in 2015 (Table 1).

The nature of the golf facility played a significant role in these trends. While public facilities significantly reduced their acreage of maintained turf, private courses did not. Private courses also had significantly higher acreages of total maintained turf than public courses did in both 2005 and 2015 (Table 2).

Acreage reductions took place largely through reductions in the sizes of fairways and roughs, but the sizes of practice areas and clubhouse grounds were also reduced significantly (Table 1, Figure 2).

For the nation overall, maintained turf acreage was reduced by 127,355 between 2005 and 2015 (Table 3). While voluntary reductions accounted for about 45% of the reductions in the acreage of maintained turf, the remaining 55% resulted from a net decrease of 681 golf facilities since 2005.

Winter overseeding

Figure 3. Projected number of winter-overseeded acres in the U.S., 2005 vs. 2015.

Winter overseeding of warm-season turf with cool-season varieties allows facilities in southerly climates — the Southeast, Southwest and Transition regions — to maintain year-round green turf and golf play.

The 69,029-acre decrease in overseeded turf from 2005 to 2015 took place largely through reduced acreage of overseeded fairways (Figure 3). The most common reasons cited for decreasing overseeded acreage were savings in money (86%), labor (74%), water (66%), fuel/energy (62%), fertilizer (61%), wear and tear on equipment (47%), and pesticides (36%).

Irrigated turf acreage

Irrigated turf acreage constituted 76% of all maintained turf acreage in 2015 (Table 4). While data on irrigated acres was not solicited in the initial 2005 survey, data from a study conducted in 2013 using comparable methods (5) suggests that the acreage of irrigated turf has been reduced by more than 10% in the past two years.

Table 4. Projected acres of irrigated turf, and percent of total maintained turf that is irrigated, 2015.

The nature of the facility had a strong influence on irrigated turf acreage, with private 18-hole facilities irrigating 85% of their acreage and public facilities irrigating 72%. Likewise, nine-hole facilities irrigated only 54% of their turf acreage, while 18-hole facilities irrigated 78% (data not shown).

Trends in non-turf acreage

Natural features

Natural features are the combined total of forests/woodland, native/undisturbed grasslands, mixed/improved grasslands, shrublands, deserts, riparian areas, buffer strips, beaches, alkaline areas and garden/landscaped areas.

In 2015, the U.S. had a total of 589,778 projected acres of natural features, constituting 26% of all golf facility acreage (Figure 4). Natural feature acreage is second in size only to maintained turf.

The acreage of these lower-input features has increased since 2005, with 46% of facilities reporting additions of natural features. It is likely that maintained turf acres have been converted to natural features over the past 10 years.

Figure 4. Projected acreage of all golf course features: maintained turf, bunkers, buildings, parking lots, water features and natural areas, 2015.

Of all natural features, forests were the dominant type, especially in areas with higher rainfall, while native/undisturbed grasslands and/or deserts predominated in areas with low rainfall (Figure 5).

Water features

Water features include open water, wetlands, streams/rivers, drainage waterways and irrigation canals.

A total of 159,072 acres of water features was projected for all golf facilities in 2015, constituting 6.9% of all golf facility acreage in the U.S. (Figure 4).

In all regions of the country, more acreage is devoted to open water than to any other type of water feature. Wetlands were the second-largest acreage water feature for all regions except the arid Southwest, where drainage waterways were more common (Figure 6).

Non-landscaped acreage

Non-landscaped acreage refers to buildings, parking lots, bunkers and cart paths.

- There were 52,632 projected acres of buildings on U.S. golf facilities in 2015, constituting 2.3% of total projected facility acreage (Figure 4).

Figure 5. Projected acreage of natural features: forests/woodland, native/undisturbed grasslands, mixed/improved grasslands, shrublands and deserts, 2015.

- There were 45,779 projected acres of parking lots in the nation in 2015, constituting 2.0% of total projected facility acreage (Figure 4).

- There were 46,136 projected acres of bunkers in the nation in 2015, constituting 2.0% of total projected facility acreage (Figure 4).

- There were 36,617 projected acres of cart paths in the nation in 2015, constituting 1.6% of total projected facility acreage (Table 5). This represents a reduction in the percentage of the golf course devoted to cart paths, which went from 1.8% in 2005, to 1.6% in 2015.

- The total median length of cart paths decreased significantly from 2005 to 2015 for the nation overall, from 17,000 linear feet to 15,000 linear feet, while the median width remained stable at approximately 7 feet (Table 5).

Trends in facility acreage

Despite large shifts in the acreage of several key golf course features, the entire size of an average 18-hole golf course facility has remained stable since 2005 at approximately 150 acres. Since 2015 no significant change has occurred in the facility acreage for nine-hole golf courses, which was 59.0 acres in 2005 and 58.6 acres in 2015 (Table 6).

The total acreage of U.S. golf facilities was projected to be 2,301,808, which represents a 4.9% or a 119,797-acre decrease in total facility acres since 2005 (Table 3). This decrease was due almost entirely to a net decrease of 681 facilities between 2005 and 2015.

Figure 6. Projected acreage of water features: open water, wetlands, streams/rivers, drainage waterways and irrigation canals, 2015.

The playing length for 18-hole facilities has increased significantly since 2005, from a median of 6,722 yards to 6,800 yards. This trend toward longer courses has been influenced by changes in the designs of balls and clubs that allow golfers to hit longer and straighter than in the past (1).

The playing length of nine-hole facilities, however, has not changed significantly since 2015, with median values of 3,100 yards in 2005 and 3,105 yards in 2015.

Trends in turf types

For winter-overseeded turf, perennial ryegrass was by far the most used turf type for overseeding in both 2005 and 2015 (Table 7). The only feature on which perennial ryegrass did not dominate was greens, where rough bluegrass (Poa trivialis) was the most commonly used turf type.

For non-overseeded turf, the frequency with which each turf type is used has stayed stable in most cases since the 2005 survey. Turf types are listed below in order of their U.S. acreages for 2015.

- The proportion of cool-season to warm-season turf has remained stable over the past 10 years (Figure 7).

- The absolute acreage of most turf types has decreased since 2005, at least partly because of the net loss of 681 golf facilities in the U.S.

- Bermudagrass (Cynodon species) made up approximately one-third (34%) of all maintained turf acreage in 2015 and continues to be by far the most used turf type in the nation (Figure 8). It is most heavily used on tees, fairways, roughs and driving range/practice areas.

Table 5. Projected acreage for cart paths, and median total length and width of cart paths on 18-hole facilities, 2005 vs. 2015. For each comparison between years, values in bold type with the lowest value followed by an asterisk indicate a significant difference between the 2005 and 2015 values at the 90% confidence level.

- Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis L.) was the second most frequently used turf type and made up 23% of all maintained turf acreage in 2015 (Figure 8). It is most often used on roughs.

- Annual bluegrass (Poa annua L.) was the third most frequently used turf type, and covered approximately 11% of maintained turf acreage (Figure 8).

- Perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.) acreage has declined slightly over time, from 12% in 2005 to 10% of all maintained turf in 2015 (Figure 8). It is most frequently used on fairways and roughs.

- Creeping bentgrass (Agrostis stolonifera) covers approximately 10% of maintained turf acreage (Figure 8) and is the most widely used turf type on greens and in nurseries. Its percentage of usage has increased slightly since 2005.

- Tall fescue (Lolium arundinaceum) now takes up 6% of maintained turf acreage, and its percentage of usage has increased since 2005 (Figure 8). It is used primarily on roughs. Tall fescues, which are more heat-, drought- and traffic- tolerant than perennial ryegrass, may have replaced that species in some areas, contributing to the decline in perennial ryegrass acreage described earlier.

Table 6. Median acreage for maintained turf and total facility, 2005 vs. 2015, for nine- and 18-hole facilities. For comparisons between years, values in the same row in bold type with the lowest value followed by an asterisk indicate a significant difference between the 2005 and 2015 values at the 90% confidence level.

- The least used of the cool-season grasses (Figure 8), fine fescue (Festuca species) represents 3% of maintained turf acreage and is used primarily on fairways and roughs.

- Zoysiagrass (Zoysia species) is used primarily on tees, fairways and roughs. Its use has increased since 2005 (Figure 8), but it still occupies slightly less than 2% of all maintained turf acreage.

- Seashore paspalum (Paspalum vaginatum) is planted primarily on fairways and roughs in southern locations, where its tolerance to high-salinity conditions is a sought-after attribute. Its use has increased slightly since 2005 (Figure 8), but the species still cover less than 1% of all maintained turf acreage.

Trends in environmental improvements

In addition to the acreage reductions in maintained, overseeded and irrigated turf detailed previously, further improvements to facility design and management can also have positive environmental impacts.

Table 7. Projected acreage of turf species used for winter overseeding in the Southeast, Southwest and Transition regions. These three regions are the only areas of the U.S. where winter overseeding is a common practice.

Pervious vs. impervious surfaces. Impervious surfaces (buildings, cart paths and parking lots) make up approximately 4.8% of an average 18-hole facility’s acreage, as opposed to the 5.1% that is made up of all buildings, cart paths and parking lots — both pervious and impervious (Table 8).

Surface runoff. Collection of surface runoff can also help decrease water pollution. In 2015, 58% of all survey respondents reported that they collected surface runoff from neighboring properties, and 74% reported collecting runoff for their own property.

Since 2005, facilities have focused on irrigation system improvements, recycling, native plantings and wildlife habitat improvement as means of further fostering environmental compatibility (Table 9). However, recycling was the only activity for which increased participation was reported in 2015 vs. 2005.

The apparently decreased frequency of environmental improvements is at least partly due to the one-time nature of some activities, such as the installation of petroleum storage tanks, wetland construction, buffer strips, etc. If they were completed several years ago, they would not have been reported in the 2015 survey.

Figure 7. Projected acreage of warm-season and cool-season turfgrasses in the U.S., 2005 vs. 2015.

In addition, given that the period from 2005 to 2015 encompassed the Great Recession, it is perhaps not surprising that golf facilities deferred non-critical improvements until budgets were restored to their pre-Recession levels.

Environmental stewardship program participation

A wide variety of publicly and privately administered environmental stewardship programs are available to golf courses. Most focus on improving golf course environmental stewardship through education, self-assessment, compliance with environmental laws and regulations, recognition/certification of achievements, and communication among the golf industry, regulatory agencies and citizens groups.

Participation in stewardship programs has changed little since 2005. As in 2005, the Audubon Cooperative Sanctuary Program has the greatest participation, but most golf courses indicated they were not involved in any of the listed programs (Table 10).

Figure 8. Projected acreage for turf species, 2005 vs. 2015.

The most commonly cited reasons for lack of participation were lack of funds (41% of respondents), practices already in place before survey (40%), or lack of time needed for implementation (39%) (data not shown).

Funding

The second phase of the Golf Course Environmental Profile was conducted by GCSAA through the Environmental Institute for Golf, and was funded by the United States Golf Association.

Acknowledgments

The information on which this article was based was published online in the journal Crop, Forage and Turfgrass Management as “Documenting trends in land use characteristics and environmental stewardship programs on U.S. golf courses” by Wendy Gelernter, Larry Stowell, Mark Johnson and Clark Brown. doi: 10.2134/cftm2016.10.0066; Date posted: Feb. 7, 2017. The content in this article was used by permission of the Crop Science Society of America Inc., Madison, Wis., USA.

The executive summary and full public report of the results of the second phase of the “Land Use Characteristics and Environmental Stewardship Programs on U.S. Golf Courses” survey will be available online (www.gcsaa.org/environment/golf-course-environmental-profile) May 1, 2017.

Literature cited

Table 8. Median acreage of all cart paths, parking lots and buildings, and the number of those acres in each feature that are impervious surfaces, for 18-hole facilities, 2015.

- Coleman, M. 2016. Long on design. Grounds Maintenance (http://grounds-

mag.com/construction/

grounds_maintenance

_long_design).

- Gelernter, W.D., L.J. Stowell, M.E. Johnson and C.D. Brown. 2016. Documenting trends in nutrient use and management practices on U.S. golf courses. Crop, Forage and Turfgrass Management doi:10.2134/cftm2015.0225

- Gelernter, W.D., L.J. Stowell, M.E. Johnson and C.D. Brown. 2016. Documenting trends in pest management practices on U.S. Golf Courses. Crop, Forage and Turfgrass Management doi:10.2134/cftm2016.04.0032

NA = question not asked previously

Table 9. Percent of all facilities that made improvements to help protect the environment in the past 10 years. For each comparison between years, values in the same row in bold type with the lowest value followed by an asterisk indicate a significant difference between the 2005 and 2015 values at the 90% confidence level.

- Gelernter, W.D., L.J. Stowell, M.E. Johnson and C.D. Brown. 2017. Documenting trends in land use characteristics and environmental stewardship programs on U.S. golf courses. Crop, Forage and Turfgrass Management doi:10.2134/cftm2016.10.0066

- Gelernter, W.D., L.J. Stowell, M.E. Johnson, C.D. Brown and J.F. Beditz. 2015. Documenting trends in water use and conservation practices on U.S. golf courses. Crop, Forage and Turfgrass Management doi:10.2134/cftm2015.0149

- Lyman, G.T., M.E. Johnson, G.A. Stacey and C.D. Brown. 2012a. Golf course environmental profile measures pesticide use practices and trends. Applied Turfgrass Science doi:10.1094/ATS-2012-1220-01-RS

- Lyman, G.T., M.E. Johnson, G.A. Stacey and C.D. Brown. 2012b. Golf course environmental profile measures energy use and energy management practices. Applied Turfgrass Science doi:10.1094/ATS-2012-0228-01-RS

- Lyman, G.T., C.S. Throssell, M.E. Johnson, G.A. Stacey and C.D. Brown. 2007. Golf course profile describes turfgrass, landscape and environmental stewardship features. Applied Turfgrass Science doi:10.1094/ATS-2007-1107-01-RS

- Throssell, C.S., G.T. Lyman, M.E. Johnson, G.A. Stacey and C.D. Brown. 2009a. Golf course environmental profile measures nutrient use management and fertilizer restrictions, storage and equipment calibration. Applied Turfgrass Science doi:10.1094/ATS-2009-1203-01-RS

- Throssell, C.S., G.T. Lyman, M.E. Johnson, G.A. Stacey and C.D. Brown. 2009b. Golf course environmental profile measures water use, source, cost, quality, and management and conservation strategies. Applied Turfgrass Science doi:10.1094/ATS-2009-0129-01-RS

Wendy Gelernter, Ph.D., and Larry Stowell, Ph.D., are the principals of PACE Turf LLC in San Diego.

NA = question not asked previously; BMPs = best management practices

Table 10. Percent of all facilities participating in environmental stewardship programs. There were no significant differences between 2005 and 2015 data.